When the Mayor of Seoul Park Won-soon was interviewed at the World Cities Summit in July after the city scooped up the 2018 Lee Kuan Yew World City Prize, he spoke as the city’s longest-serving mayor in his third term.

“A pedestrian-friendly and bike-friendly city is the most important part of our direction,” said the former human rights lawyer, longtime civic activist and founder of the nonprofit watchdog People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy.

“It’s very good for the health of citizens, because they are working there on an everyday basis. We are trying to change it in many ways, especially transforming the car lanes into pedestrian friendly lanes or bike lanes,” he said.

“We established thousands of bike stations with more than 20,000 public bikes all across the city. We also expanded the bus rapid transit system in many main boulevards, recently we changed the main street in town into a BRT system with two lanes of bikes,” said Mayor Park.

Bold, iconic decisions that have become urban planning legends— like the pedestrian-centric Cheonggyecheon Restoration Project and Seoullo 7017 Skygarden— headline the city’s transformation from the aggressive, top-down industrialization of the Asian Tiger economies’ heyday to the liveability-centric participatory democracy it is today.

They also feed into Seoul’s longstanding fight for better air quality.

In the last 50 years, the 2000-year-old city has witnessed a steep increase in population, now standing at over 10.1 million, and vehicle numbers have soared in classic tandem with urbanization and industrialization.

Seasonal smog and occasional crisis-level spikes in air pollution in the country and the capital have evoked concern in South Koreans, and a recent study by NASA and the National Institute of Environmental Research confirmed that 52 per cent of particulate pollution in Seoul comes from domestic sources.

In March this year, two months after several spikes in air pollution catapulted South Korea into the ranks of the world’s most polluted countries, Seoul’s metropolitan government banned schools from conducting outdoor classes whenever PM2.5 levels hit 76 micrograms per cubic metre (µg/m³) or higher for two hours or longer and advised reduced hours or class cancellations if that figure reached 180µg/m³.

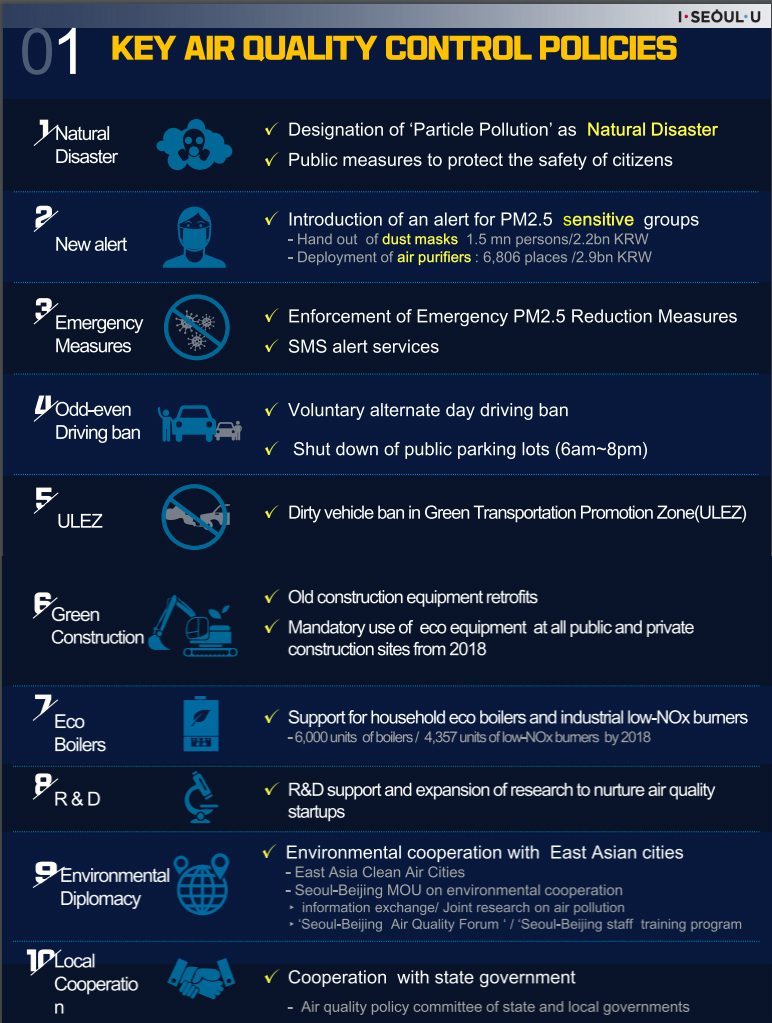

In its search for solutions, Seoul has thrown the book at air pollution. Some of its most recent policies include:

• a car labeling scheme, announced in April 2018, that will classify cars into five different emissions categories, which come with various benefits, incentives and penalties;

• a citywide dirty vehicle restriction when emergency ultrafine particle (PM2.5) reduction measures are enforced (between 6am and 9pm), which kicked in on 1 June 2018, part of a broader emergency response plan;

• almost tripling monitoring spots by 2020 to boost its monitoring efficiency, particularly of non-compliant vehicles;

• the establishment of an ultra-low emissions zone, called the Green Transportation Promotion Zone; and

• public information, education and incentives to support the implementation of an economy-wide set of measures.

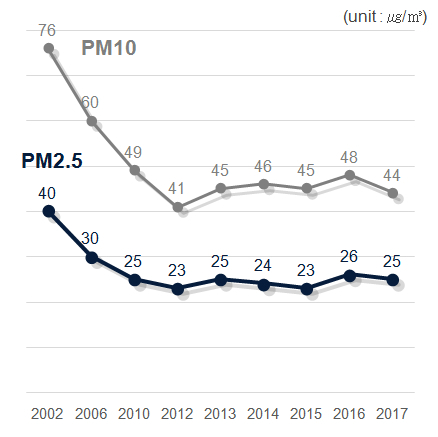

These measures likely contribute to the Seoul Metropolitan Government’s goal of reducing concentrations of PM2.5 emissions from 25μg/m³ in 2013 to 20μg/m³ in 2018, six years ahead of the central government’s goal of 20μg/m³ by 2024.

It also aims to cut concentrations of PM10, PM2.5, nitrogen dioxide and ozone in half compared to what business-as-usual would produce in 2024.

At last count, the World Health Organization listed Seoul’s annual mean of PM2.5 concentrations (very fine particulate matter about the size of some virus molecules) at 26µg/m3, both above the WHO’s guidelines for healthy air.

At this week’s Northeast Asia Forum on Air Quality Improvement in Seoul, UN Environment Executive Director Erik Solheim praised Seoul’s air quality action and welcomed it to the BreatheLife campaign (see video), while thanking the city and representatives of other Asian cities for their efforts to tackle air pollution.

He cited the Seoul’s efforts “to move to a solar city, providing millions of households with solar panels, increasing the number of e-vehicles on the streets and restricting access to diesel vehicles, and citywide campaigns to reduce the use of single-use plastic”, calling them “tremendous progress towards the kind of future we all want”.

Seoul also hopes the latest measures will help to break through a ceiling.

“The air pollution level in Seoul is on the decline for the long term, but the particulate matter levels have been stagnant since 2012,” said Seoul Metropolitan Government’s Director of Air Quality Management, Kwon Min.

The situation has made Seoul a willing test-bed for novel solutions: a pilot drone programme to monitor industrial emissions and ensure they do not breach air quality standards, the use of big data to optimize solutions and help citizens make a seamless transition to public transport, and free public transport when the city declared air pollution emergencies.

The last measure didn’t quite work as planned: at an estimated cost of 6 billion won ($5.65 million) per day, it barely moved the needle, leading to a drop of just 1.8 per cent in traffic, and was subsequently dropped, reinforcing Mayor Park’s long belief in putting citizens at the centre of urban decision-making.

Park brought this consultative approach to dealing with foreign sources of air pollution, recently strengthening a partnership with Beijing on air quality improvement. In March, Park and Mayor of Beijing Chen Jining witnessed the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding to promote environmental cooperation between the two capital cities, with a focus on clean air actions– both undoubtedly bringing many stories of policy success and challenges to the table.

Follow Seoul’s clean air journey here.

Banner photo by Jens-Olaf Walter, used under CC BY-NC 2.0.