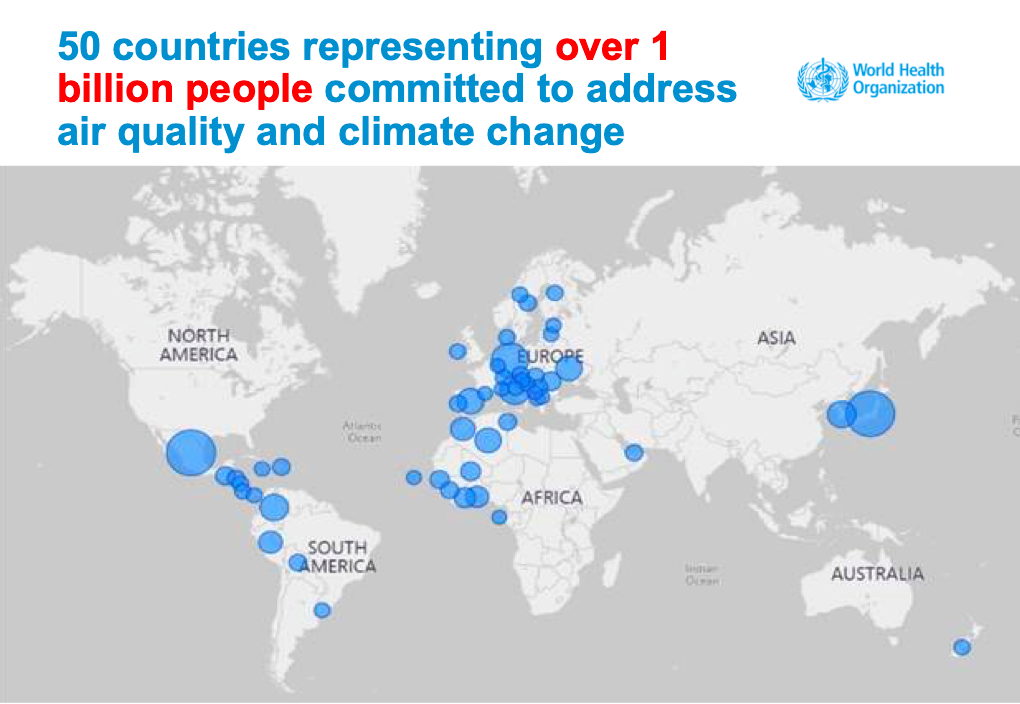

More than one billion people across the world now live in countries that have made a commitment to pursuing “safe” air quality by 2030 as part of their climate change plans, according to the World Health Organization.

Fifty-three national governments have now signed up to the Clean Air Initiative, which, among other specifics, commits them to achieving WHO air quality guideline values and evaluating lives saved, health gains and savings to health systems of policies.

The pledge gained traction at this year’s Climate Action Summit in September, reflecting the rise of awareness of the impacts of climate change on human health and health systems— but also of the close links across climate action, air pollution and human health.

“Health is paying the price of the climate crisis. Why? Because our lungs, our brains, our cardiovascular system is very much suffering from the causes of climate change which are overlapping very much with the causes of air pollution,” said WHO Director, Department of Environment, Climate Change and Health, Dr Maria Neira.

Commitments to reach WHO air quality guideline values, and align climate and air pollution policy, by 2030. Image: WHO.

As countries meet in Madrid, Spain, for the latest iteration of the Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP), the WHO was joined by other organizations— from the International Federation of Medical Students’ Associations, which represents the world’s future doctors, to UN agencies like the World Meteorological Organization and UNICEF— urging action from all parts of society to act more swiftly on climate change in the name of human health, as decades of evidence establish solid links between the two.

“It’s absolutely essential that as a health community, we come here and speak up, and say, ‘this is not just an environmental issue, important though that is; this is not just an economic issue, important though that is— it’s the fact that climate change is undermining all of the progress we’ve made in global health in recent years,” said WHO’s Coordinator, Climate Change, Dr Diarmid Campbell-Lendrum, in an interview with Connect4Climate.

It turns out, though, that tackling the challenges of climate change, air pollution and other aspects of sustainable development together makes economic sense anyway.

The 2019 Emissions Gap Report by the UN Environment Programme, a major annual stocktake that compares where greenhouse gas emissions are heading versus where they need to be, highlights “a growing body of research has documented that ambitious climate action, economic growth and sustainable development can go hand-in-hand when well managed”.

It cites a study by a 2018 analysis by the Global Commission on the Economy and Climate, which estimates that ambitious climate action could generate US$26 trillion in economic benefits between now and 2030 and create 65 million jobs by that time, while avoiding 700,000 premature deaths from air pollution.

The report also mentions a study that finds that “a global fossil fuel phase-out could avoid over 3 million premature deaths each year from outdoor air pollution, or well over 5 million premature deaths per year if other human-driven greenhouse gases” are cut, including emissions from agriculture and industry that don’t come from burning fossil fuels, such as methane.

The annual costs of tackling those challenges together were found to be about 40 per cent lower than the total policy costs of overcoming each of them separately.

The 2019 Lancet Countdown on health and climate change found that if the improvement in particulate air pollution from human activity experienced by Europe from 2015 to 2016 stayed the same over the course of a person’s life, it would lead to an annual reduction in years of lives lost worth €5.2 billion.

Globally, two-thirds of health damage from outdoor air pollution comes from the burning of fossil fuels.

“Meeting the Paris Agreement goals would save about 1 million lives a year by 2050. We can’t afford not to do it,” said Dr Campbell-Lendrum.

The billion people covered by the Clean Air Initiative commitment does not yet include those led by the 87 subnational governments who also committed, some of whose national governments have not signed it.

Several subnational government leaders, including that of Glasgow, the host of the 2020 COP, spelled out their ongoing efforts and plans to decarbonize their economies, describing cleaner air, greater social justice and more active mobility as being among the “co-benefists”, all of which get to the heart of prevention of the world’s top and rising non-communicable diseases and killers.

Yet, it is still not the norm to cost and count the health co-benefits when decisions with high sunk costs and decades of impact are being made— decisions in areas of urban planning, built environments, energy sources, infrastructure and networks, transport, among others— something the Clean Air Initiative commitment includes.

“If we can hold countries to that commitment, we can save millions of lives as well as combat climate change,” said Campbell-Lendrum.

There’s more happening now on climate and health at COP25 at the Global Climate and Health Summit, Madrid, Spain, 2019.