This is a Health Policy Watch story.

Delhi declared a public health emergency as air pollution levels soared on Friday, while Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal said that the mega-city had “turned into a gas chamber”.

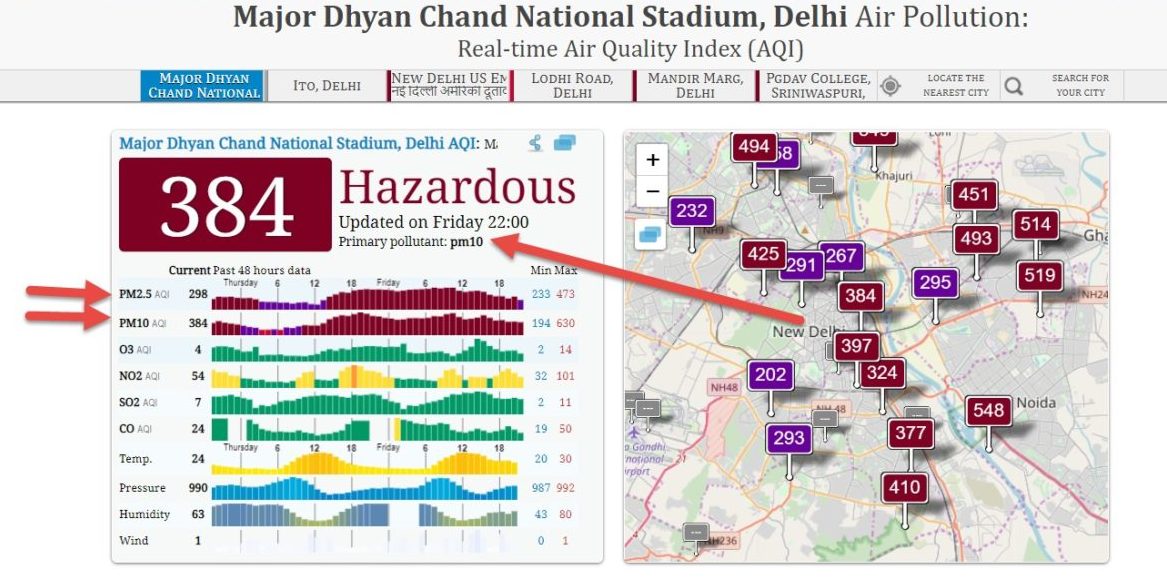

According to official government monitoring stations, levels of tiny PM10 air pollution particles had risen as high as 20 times WHO Air Quality Guideline levels in parts of the city over recent days. As of Friday evening, concentrations of the small particles, among the most health hazardous pollutants, were averaging 300-500 micrograms per cubic meter of air – or 6-10 times the WHO 24-hour guideline of 50.

Air pollution levels at 10 p.m. Friday night near Delhi national stadium, showing the combined data of three government monitoring networks, CPCB, DPCC and SAFAR

To cope with the emergency, the Delhi Government launched an unprecedented mass distribution of some 5 million masks to school children, banned construction, cancelled school until Tuesday and placed sharp limits on vehicle travel with an “odd-even” scheme permitting private vehicles to travel only on alternate days, as per the digits of their license plate.

“In the interest of protecting our children, it has been decided to keep all the schools – Government, Government-aided, and Private – in the National Capital Territory of Delhi closed until November 5th 2019,” said the Office of the Deputy Chief Minister in a decree published on Twitter.

Kejriwal blamed the increase in “stubble burning” in neighboring regions of Punjab and Haryana for Delhi’s recent spike in air pollution levels. The practice of burning leftover straw after grains are harvested is a rapid method for farmers to clear their fields, but also sends huge plumes of smoke and biomass pollution into the air, spreading for hundreds of kilometers.

“Delhi has turned into a gas chamber due to smoke from crop burning in neighbouring states,” said the minister on his Twitter feed. “It is very important that we protect ourselves from this toxic air. Through pvt & govt schools, we have started distributing 50 lakh [5 million] masks today I urge all Delhiites to use them whenever needed.”

But scientists and civil society activists maintained that no single source can be blamed for the city’s chronic air pollution problems, which peak in the early winter every year. Rather, a combination of urban and rural sources create a perfect storm of pollution that hovers over the city and the wider region. These also include pollution from domestic wood/biomass stoves; unfiltered smokestack emissions from Delhi area power plants; urban waste incineration; construction dust; the rampant use of polluting two-stroke engines in two-wheeler vehicles; as well as the seasonal “Diwali” festival of lights – where setting off firecrackers is a traditional ritual.

(left-right) Delhi sky on Sept 27, Delhi sky on Nov 1, Kejriwal distributes masks to school children in air pollution emergency

“We know that the air pollution comes from at least 8-10 sources. We want the government to address all of these and not just cherry pick,” said Joyti Pande Lavakare an activist journalist who runs the organization CareForAir.org and is completing a book “Breathing Here is Injurious To Your Health” to be published early next year.

She said that her organization had grave misgivings about the mask distribution scheme – whether the masks would in fact have adequate air pollution filters, and whether they would really reach 5 million people. On top of that, unless masks are properly fitted they won’t work at all, even as a stopgap measure – and for many children the masks will just be too large.

“Masks are not a solution,” said Lavakare. “And they may give you a false sense of security. Masks are more of a visual. I am for masks because they make an invisible problem visible; they are an immediate necessity, but only if they fit well. And people who have asthma will feel suffocated if they wear a mask. The only real thing to do in an emergency is to stay indoors and keep respiration rates low.”

However, she added that Delhi’s chronic air pollution issues, which peak annually in November and December, required more than “short-term band-aid measures”, adding that leadership from the very top of the political spectrum was needed.

“I want the prime minister [Narendra Modi] to actually lead this issue; currently it is actually rudderless and leaderless. You cannot have a prime minister who is talking about clean India without talking about clean air. And yet he has been strangely silent on this issue. In no forum has he talked about air pollution,” she observed, noting that each air pollution source has a longstanding history of failure behind it.

For example, a Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Climate Change decision to install modern pollution filters on Delhi area power plants by 2017, potentially reducing average air pollution levels by about 30% in northern India, has been delayed for over two years by the Ministry of Power and could remain stalled until 2020 if the latter Ministry has its way. Three-wheeler vehicles, auto rickshaws, which provide much of the Delhi’s public transport, still run on heavily polluting two-stroke engines. And regional pollution from crop-burning has intensified as local varieties of nutrient-rich food crops were gradually replaced by rice, produced mainly for export and sucking up scarce water resources, says Lavakare.

Lavakare is, however, more hopeful that the debate about air pollution is growing stronger and public opinion more informed about the multiple health risks air pollution creates – which according to WHO range from spikes in hospital admissions and death rates during air pollution emergencies to stunted childhood lung development, reduced long-term life expectancy and higher premature mortality from stroke, heart disease, lung cancer, and respiratory disease as a result of chronic air pollution exposures. Recent evidence has also pointed to serious air pollution impacts on the brain development of infants and young children.

“When we started to build awareness three years ago, we were told by top government officials that it was a rich person’s problem. The point they were missing was that it is a bigger social inequity for the disenfranchised and the homeless people who don’t have the privilege of having masks, air purifiers and four walls to keep the pollution out.

“Now, the government can no longer say this is just a rich person’s problem. It’s clear that it is everyone’s problem. And the Indian media is finally fully supportive,” said Lavakare. “No one [politician] cares if it it really is creating toxic impacts on health, but people do care if it gets them votes. And at least that is a start. But we need a tipping point – like the film ‘Under the Dome‘ which got China to do something.”

It was clear that after the fifth day without sunlight, average Delhi residents were crying for change.

“No air circulation. Eyes burn. Breathing is difficult. Can’t even go out for a walk. Sick!” commented one commentator on Twitter.

One Indian parliamentary member, former cricketeer Gautam Gambhir critiqued the high-level response and urged Kejriwal to check how many construction sites are complying with the new regulations on the ground.

A high profile, India-Bangladesh cricket match planned for Sunday provided a lightning rod for a lively debate over the air pollution emergency, with critics calling for the match to be postponed because of the irreversible health impacts exposure to such high air pollution levels can have, but sports authorities resisting.

UN Goodwill Ambassador and Indian actress Dia Mirza blasted the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) decision to continue hosting the India versus Bangladesh match on November 3rd, despite the dismal air quality.

“BCCI please stop hiding your head in the smog,” she tweeted. “This air harms players and the people that come to watch these games.”

I thank #Delhi for closing schools till the 5th of November. Now think of all those little children and elderly living in street situations and inhaling toxic fumes daily. Ask WHY are 14 of the most polluted cities in India? Change will be possible when we acknowledge the problem pic.twitter.com/pcgZep7gIx

— Dia Mirza (@deespeak) November 1, 2019

One cricket commentator drolly observed that perhaps the BCCI’s decision to not cancel the match was strategic, saying that “Indian cricketers are better used to such bad air than any other cricketing nation.”

Indian players, used to playing in environments with poor air quality, will be able to better tolerate the ghastly air pollution levels and play better than athletes who are used to training in climates with lower levels of air pollution, he reasoned.

“India shall, through series openers scheduled in Delhi’s toxic air, introduce pulmonary disintegration to the game,” said Siddharth Monga in a piece for ESPN.

Image Credits: www.aqicn.org, Arvind Kejriwal.